Sophia Rosamond Praeger was an incredibly influential Northern Irish artist, who has been largely forgotten in the years after her death. Throughout her seven decades of work, Praeger created art all over Northern Ireland, from hospital and gardens, to tombstones and memorials. Her philanthropy, advocacy, and involvement in the Suffragette movement and many of the well-established societies of the city made her an important figure in Belfast’s past, but her legacy has been lost in the decades since her death.

Sophia Rosamond Praeger, or simply “Rosamond” as she preferred, was born in Holywood, County Down on the 15th April 1867. Her Father, Willem Emilius Praeger was a linen merchant who immigrated from a wealthy Dutch family, and her mother, Maria Patterson, came from a wealthy Belfast family. Before her father’s unexpected death in 1881 and her education at Sullivan Upper School, Rosamund was educated at home. She grew up with her five brothers in what was considered a very “cultured” household:

Praeger grew up in a liberal and cultured environment and her family thought little of her friendship with the local stonecutter John Lowry, in whose stonemason’s yard she cut her first piece of marble as a teenager

Joseph McBrinn. 2024

Once her mother recognised Rosamond’s passion for creating art, she sent her to the Belfast Government School of Art in 1885 to help expand her abilities. Whilst at the school, she was trained by a famous watercolour and oil paint landscape artist, George Trobridge, who commonly pushed artists to draw inspiration for art from nature. Praeger’s love for nature can be seen all throughout her career. When she joined the Ramblers Sketching Club in 1886, and was one of the first woman to do so! This love of nature was ever-present in her earlier work.

Praeger’s education would see her move away from Belfast, when she attended prestigious art schools in both London in 1888 (The Slade School of Art) and Paris in 1893 (the Academie Julian). Throughout her time at these prestigious schools, she received multiple scholarships and prizes for her art, and became one of the leaders of what was referred to as the “New Sculpture Movement” which came about in the late 1800’s. This movement was seen as a more dynamic and “true to life” compared to the French art movements which inspired it, and offered exciting new ways to reimagine classic sculptures.

Whilst her education helped shape Praeger’s skills, her own unique style blossomed after her education, with her work shown at art shows and galleries throughout the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. In some of these exhibitions she showed a mixture of drawings, prints and even embroidery work. She was heralded as a poet, a writer, a designer and a painter, but her favourite profession was as a sculptor.

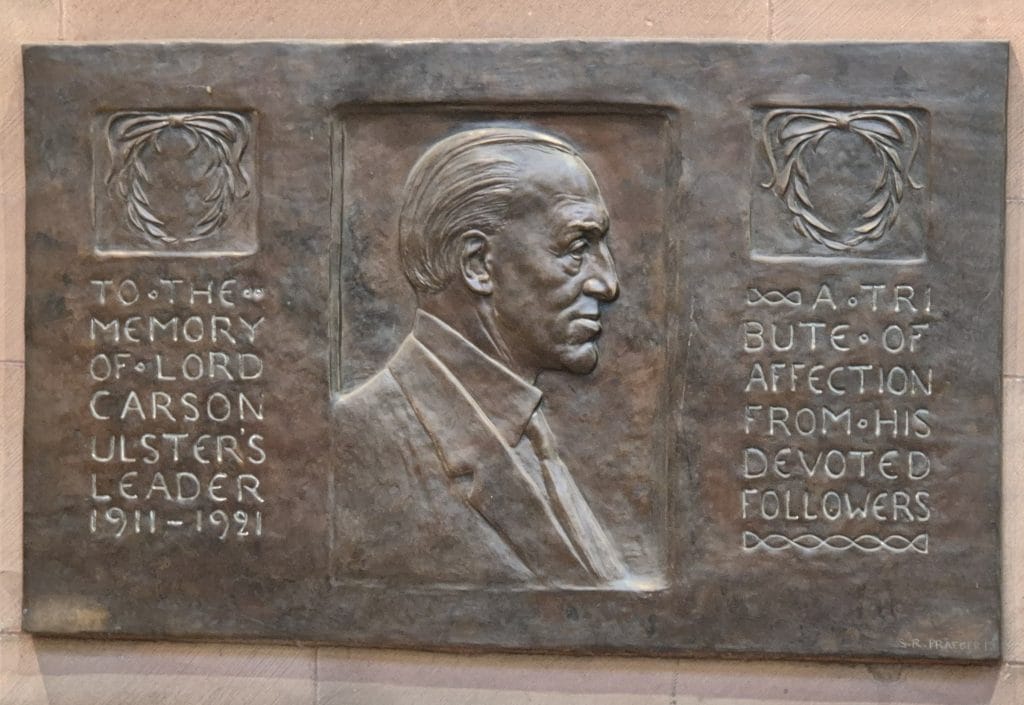

Praeger returned to Belfast in 1893, taking on multiple sculpture based commissions around the city, from private commissions and war memorials, to works in churches, hospitals and libraries. She used multiple mediums throughout her work and made larger-scale projects like fountains and garden sculptures for the wealthy, all the way to making small pieces, such as children’s toys. She also demonstrated an innate ability for graphic design, creating posters, logos and even illustrations for children’s books.

It was through graphic design that Praeger’s artistic abilities aligned with her personal views and advocacy- a place from which she could channel her art for the greater good. She created posters and cards for the Suffrage Movement in Ireland and England. She regularly attended ‘Suffrage Atelier’ in London dedicated to creating art which advocated for the rights of women and provided art for a number of groups, such as the Irish Women Worker’s Union and Cumman na mBan (or the Irishwomen’s Council). She also ran a toymaking workshop in Holywood to raise money for the Irishwomen’s Suffrage Federation. Praeger’s work demonstrated how vital art was to the success of organisations and movements in the early 20th century, with her work often conveying a level of humour and sarcasm along with social commentary.

Praeger became one of the most prominent voices advocating for women in the arts, and used her platform to support other young women in arts whenever possible. During her school years, she was friendly with fellow artists such as Ellen Rope, Cecilia Harrison and Esther Moore, and was a public supporter of their work. A consistent advocate and voice for women in art as well as female emancipation, Praeger advocated fervently for other female artists to be included in exhibitions and displays. In one instance, Praeger lobbied for the Ulster Museum to display works by artist Mary Swanzy, with Swanzy later showing support for one of Praeger’s understudies, Wilhelmina Geddes, by purchasing some of her works. While Praeger’s career was flourishing, she made a point of supporting other women with their careers too!

Praeger took Wilhelmina Geddes, a promising young artist from Leitrim who was being educated in Belfast, under her wing saying she was “one of the most original and talented artist Ireland has yet produced” The acclaimed stained glass window “Children of Lir” created by Geddes was commissioned by the Ulster Museum after Praeger persuaded the curator to commission the work . Local poet and fellow art-lover John Hewitt noted that Praeger once sent him a letting in 1951 criticizing the fact that a survey he had published on art in Norther Ireland had not even included Geddes and advocated for her work to be recognised. Geddes and Praeger remained close and even held joint art exhibitions until Geddes left Belfast to pursuer her career abroad.

Praeger was an active member of the wider community in Belfast and Holywood throughout her glittering seven decade career. She published some of her Poetry in 1947. She was a member of the Naturalist’s Field Club, the Gaelic League and was a founding member of the Guild of Irish Art Workers. Her appreciation of nature continued throughout her life and she was a frequent donor to the Ulster Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the National Trust, as well as the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. In her will, she left her Holywood studio for “the benefit of the Children of Holywood”. Her diverse interests were well represented in her art, which constantly drew on inspirations that she saw in the world around her. For her work, Fairy Fountain, Praeger used photographs taken by local photographer and fellow member of the Naturalist’s Field Club, A.R Hogg: the subject- the impoverished children of Belfast.

Rosamond Praeger retired from her art career in 1952, aged 85. Her last piece, titled Johnny the Jig, which depicted a young child playing the accordion, can still be found near the maypole in Holywood. She would died a few years later on the 17th April 1954 in her cottage in Cultra, shortly after her 87th birthday. She was buried with her parents and two of her brothers, and her name is now inscribed beside theirs, on a headstone of her own design.

During her life, her work was celebrated. It was displayed in multiple galleries across Britain, Ireland and further afield, such as Paris. She was awarded multiple accolades, including becoming an honorary MA from Queen’s University Belfast and an MBE in 1939. In the decades after her death there have been a small number of art exhibitions that featured her work, however, her impact over the years has waned, with many of her works deteriorating or being lost. While there may be a few homages to Praeger in Holywood, such as the Praeger room in the local library, as well as Praeger House in her Alma Mater of Sullivan Upper, there are few public spaces dedicated to her memory or impact within Northern Ireland.

Perhaps the most poignant example of the deterioration of her legacy is the family headstone. On the headstone, there are two figures; Hope and Memory. By 1992, both were badly damaged and in danger of crumbling away. A fundraising campaign for the restoration of her gravestone was made, which made reference to Praeger’s dedication to the arts, and the numerous individuals she inspired through her work and her philanthropy. During this period, local historian Derek McCartney stated: “It is literally going to pieces. Miss Praeger’s name is fading badly. Hope is beginning to go and Memory will eventually follow suit.” An ironic, but perhaps fitting metaphor for how quickly memory and legacy can be lost if it is not preserved. Fortunately, in the years since this fundraiser, there has been a greater awareness and appreciation of Praeger’s work, and in 2007 Queen’s University Belfast curated an exhibition solely focused on her own work. When covering the exhibition, the Belfast Telegraph noted that Praeger was “one of the first major artists to emerge from Belfast in the late 19th Century”, continuing

Always somewhat neglected by mainstream art history, her work remains a popular public favourite although, in general, she is perhaps the least well known of Ulster artist.

It is an indication of the up-hill struggle faced by many women in the arts during this period, that someone who broke down barriers, and was heralded by her peers and changed the landscape in Ireland and England for women in the arts, could be so easily forgotten: whilst many of her contemporaries found greater appreciation after their death. This was perhaps best highlighted in 1941, when Rosamond Praeger was elected the first female president of the Ulster Academy of Arts. The artist who nominated her was none other than Sir John Lavery. Both were immensely talented artists, who left a significant body of work, but whereas Lavery has maintained a significant presence in Belfast and Glasgow in the decades after his death, Praeger’s influence has waned. Despite Praeger’s body of work, including assisting with the internal artwork of Belfast Cathedral, she was overlooked for other commissions. For example, she applied to be one of the sculptors chosen to decorate the gardens and interior of Belfast City Hall, but the commission was eventually awarded to an all-male team from a London firm. It is interesting to imagine City Hall designed to Praeger’s unique style. Would her legacy and memory be better preserved had she been commissioned on a marque project in Belfast?

Philanthropist, community-leader, advocate, Suffragette, poet, sculptor, artist: each of these describes one of the many hats of a truly remarkable woman. But perhaps most remarkable is that despite her impact on many facets of Belfast society, her life and legacy, along with many of her sculptures have been weathered by time, and it is only in the last 20 years or so that she has found her place amongst the greatest of our artists.

About the Author:

Brooke Norgaard is a MA student at Queen’s University Belfast in the Public History program. She obtained her undergraduate degree in History at the University of Sioux Falls with a focus in history teaching. Her focus areas are women’s history, the Salem Witch Trials, dark tourism, and carceral history. Norgaard has spent years working at various history museums in the United States and is currently an intern for the North Belfast Heritage Cluster. All research has been conducted to a high academic standard and has been fully referenced. If you would like to know more about a story or piece of research, or if you wish to tell us about your own story, email us at: archiveproject@nbheritagecluster.org