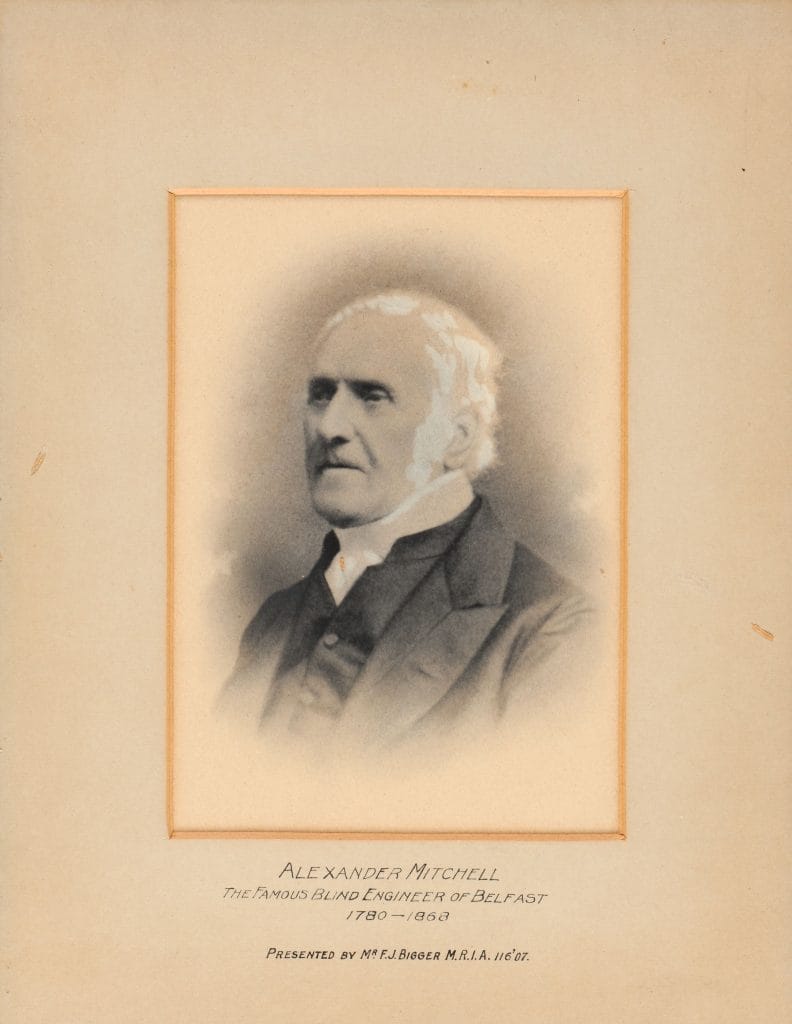

Alexander Mitchell- The Blind Engineer of Belfast.

Cemeteries are often places of reflection and serenity. When you walk amongst the graves in Clifton Street Cemetery you are surrounded by history, and echoes of the personal stories of those buried around you. Certain graves demand your attention, with the ornate decoration or their sheer size drawing the eye. For example, when you approach the grave of Mary Ann McCracken, you are first drawn to the prominent stone obelisk of the Luke Family Mausoleum before arriving at the modest and comparatively nondescript grave of Mary Ann immediately beside it. With so many of Belfast’s most prominent citizens of yesteryear buried in Clifton Street Cemetery, it is easy to simply walk by a vacant wall plot without much thought, moving between the graves of the successful linen merchants such as Charters and Ewart. There is nothing in ‘Plot 76’ that speaks to the importance of the individual buried there, nor to the hundreds of lives his creation may have saved!

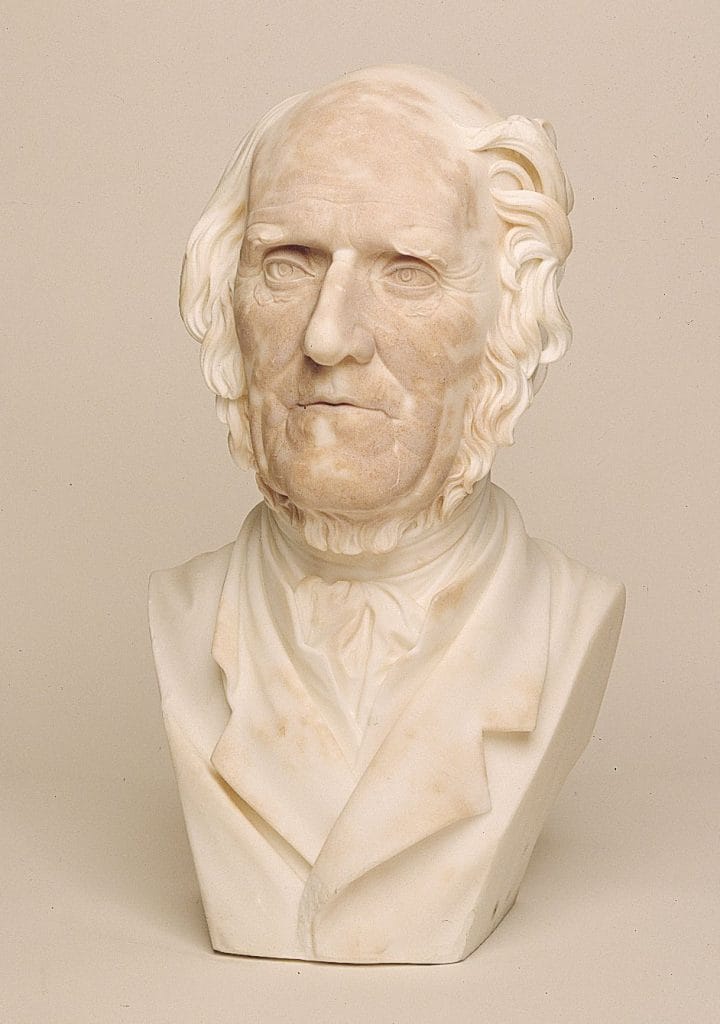

The person buried in the unmarked wall plot of Clifton Street Cemetery is Alexander Mitchell. He may not be a household name, but of all the individuals researched for the website, he is by far the most widely researched by other historians.

Alexander Mitchell was born on the 13th April 1780 in Dublin, the eighth of thirteen children. His father, William Mitchell, originally from Belfast, was inspector general of barracks in Ireland. The family settled at Pine House in 1788, with Alexander attending a school nearby. After his father’s death, his mother, Jane, moved to Eglinby Cottage in Ballymacarrett. During this time, he attended Belfast Academy, which was still situated on Academy Street under the direction of Dr William Bruce, near the heart of the city, where he demonstrated his keen intellect and affinity for the sciences.

Throughout his time in Belfast Academy his eyesight deteriorated. Smallpox had damaged the optic nerve. By 16 he had lost the ability to read and by his early twenties he was blind. Braille had not been invented at this time (first invented in 1824), but he was determined continue his studies, and with the help of his wife and children studied mechanics and mathematics.

Using money left to him by his father, Alexander started up a successful business making bricks. The business’ success can be attributed to his creativeness and ingenuity as an engineer, as he invented several machines which he then used in the brick-making trade (along with other items such as musical instruments, wooden clocks and windmills!). As the business grew, he designed and developed premises on Alfred Street, Gloucester Street, Sussex Place and Joy Street:

He was not only his own architect, but his own surveyor and, we believe, the contractors whom he employed had abundant reason to be aware that, although labouring under the want of sight, there was no better judge of materials and workmanship.

Northern Whig. 27 June 1868

Alexander continued working in his brick-making business until 1832, when he began developing an invention that would save many lives around the world: the screw pile lighthouse.

Mitchell was adamant that navigating shoals and sandbanks could be made safer if lighthouses were able to be built on the shifting, evermoving sands of Belfast Lough. He modelled his invention on an ordinary corkscrew, which helped the piles penetrate deeper into difficult terrain. These screw-pile lighthouses were cheap and easy to build but could be constructed on the most difficult terrain.

These lighthouses were often in the shape of hexagons or octagons, with a single central pile that was driven nearly 7 metres down into the river bed or ocean floor. Despite initial issues in getting his invention patented, in 1838 he was invited to lay the foundations of the first screw-pile lighthouse at Maplin Sands in the Thames Estuary. Such was the success of his invention, further lighthouses were commissioned in Morecombe Bay (near the Lake District), and in Belfast Lough: Mitchell’s invention was a success!

Not content with being the mind behind the invention, Mitchell was often heavily involved with building his inventions. In his 60’s and completely blind, he as often seen climbing ladders and scaffolding high above the sea to inspect the work being done. He apparently argued that it was safer for him to do so, because others were able to see the terrifying heights at which they worked! His fingers had become so sensitive from his decades of work, that he was able to detect flaws in workmanship and materials, that may have been missed by other surveyors. He took great pride in his involvement, despite the dangers and his family’s protests! On one occasion, after falling into Belfast Lough, he was hauled back on board and was described as “cool and collected, with his hat lost, but his stick in his right hand”.

By all accounts, Mitchell’s approach to his work is in keeping with his personality. He was well liked and respected by his peers who recognised the impact and magnitude of his inventions. In 1837 he was made an associate of the Institute of Civil Engineers, and in 1848, he was elected a member. He was awarded the Telford Medal for his paper on the Screw-Pile Lighthouse, and a medal at the Paris Exhibition in 1855.

Mitchell was also a member of the society of United Irishmen in his early life. His obituary states that he was a supporter of full, fair representation for the people of Ireland in Parliament, but he withdrew from the society when they became more of a ‘secret association’.

He was also a keen musician and was fond of traditional Irish songs. He took up a position of the musical committee on the Belfast Harp Society, and was friends with the society’s founder, Edward Bunting. Mitchell also brought his engineering expertise to his love of music, apparently inventing several different musical instruments. During the construction the lighthouses, Mitchell would often join with the workmen in singing sea shanties as they went about their work.

He was extremely fond of music, and was no mean proficient in it. He understood its theory and was well versed in its history. It was no ordinary treat to hear his voice mingled with others that are now silent like his own, in the sweet melodies of the olden time, which he so fully appreciated.

Northern Whig. 27 June 1868

Alexander Mitchell died at Glen Devis in 1868 on 25th June, at the home of his daughter Margaret. He is buried in Clifton Street Cemetery, in an unmarked wall plot-plot 76. There is no clear reason given for the lack of a headstone, and burial records show the purchase of the plot in 1845 as well as his burial in 1868. Despite the mystery around his unmarked grave, Alexander Mitchell has been well documented in other historical journals; many of which helped inform this research piece. His story touches on a semblance of romanticised irony: the blind engineer whose creation helped others see in dangerous waters. His skill and ingenuity were admired by all, but it is his character and his diverse interests that are so warmly remembered in his obituary:

Mr. Mitchell was a man of genial heart and kind sympathy. He loved to converse with the friends who called to see him, even though their visit might interrupt some train of thought, some course of reading or of dictation…He seemed to forget nothing. History, poetry, philosophy-even points of law that appeared to lie quite out of his way- he seemed to have at his finger’s ends; and though he willingly poured forth his own intellectual wealth he was- what some richly furnished men are not- a good listener… He was, indeed, a man to be loved and honoured as well as to be admired.

…There are few whose career of life is so long as his has been; and none can be more estimable or more esteemed than Alexander Mitchell…his virtues will live in the memory of his friends; and his useful and benevolent achievements will hand his name down to late posterity.

Northern Whig. 27 June 1868

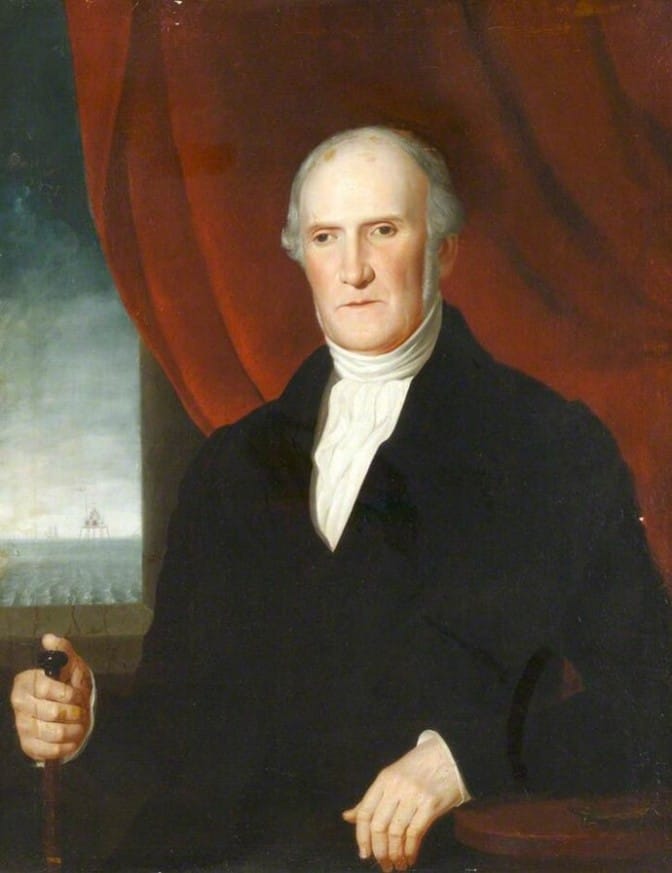

His portrait is amongst those in the Harbour Commissioners Office, painted by Richard Hooke, (who also painted portraits of the Benn Brothers), with Dundalk Bay and it’s screw-pile lighthouse behind him. In spite of the mystery surrounding his grave, he was fondly remembered by his peers.

Belfast has reason to be proud of many of her sons, but over no one of all those has she more cause of exultation than over Alexander Mitchell

Northern Whig. 27 June 1868

About the archivist:

James Cromey is the Archive and Project Coordinator for the North Belfast Heritage Cluster. He has a background in Victorian, Industrial and Medical History and has received degrees from the University of Glasgow and Queens University Belfast. All research has been conducted to a high academic standard and has been fully referenced. If you would like to know more about a story or piece of research, or if you wish to tell us about your own story, email us at: archiveproject@nbheritagecluster.org